KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— More than four of every five of the nation’s state legislative seats will be on the ballot this year.

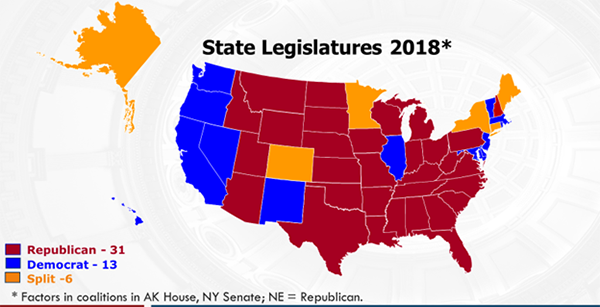

— The usual midterm presidential penalty extends to state legislative seats, where the presidential party loses an average of more than 400 state legislative seats each midterm.

— On average, 12 chambers flip party control each cycle. Democrats should net chambers but may fall short of that average.

— One possible outcome in November is that Democrats pick up hundreds of seats but manage to wrest control in just a few legislative chambers because the GOP holds such big majorities in many states.

— The nation is likely to elect a historically high number of women state legislators. About one in four state legislators are women currently.

The battle for the statehouses

National political coverage in 2018 is focused on the political destiny of Congress, naturally enough. The strong consensus is that Washington is headed for divided political control again, meaning continued gridlock and possibly even more unproductive partisan warfare.

That’s why the 6,000+ legislative seats on ballots in 46 states are critical to the direction of the country. Policy innovation has become almost exclusively the domain of the states in contemporary American politics (and cities, if we are being totally fair). Legislators and governors work together, often across party lines, to tackle issues such as the opioid crisis, infrastructure, immigration, health care, climate change, workforce development, modernizing tax systems, education, sentencing reform, net neutrality, etc.

Going into the election, Republicans are in the driver’s seat of state partisan control and are using their majorities to enact GOP policies wherever they can — which is throughout much of the nation. In concert with the surprising Donald Trump victory two years ago, Republicans emerged from the 2016 election with an advantage in the states unlike anything they had enjoyed in nearly 100 years.

Democrats are banking on the wisdom of Sir Isaac Newton, who declared in his universal law of gravity that “what goes up, must come down.” History, data, and political tea leaves all indicate that this will be a recovery year for Democrats in the states. With less than a month until votes are tallied, the question is how far up can Democrats go from their pre-election low point — and how far down might Republicans fall from their current heights.

Plus, 2018 is the first “redistricting 2020 election.” State elections take on added import this year because the more than 800 legislators and 34 governors chosen in November will be directly involved in the 2020 redistricting cycle, beginning when census data is reported in 2021.

What seats are up in 2018?

Voters will choose legislators in 88 of the nation’s 99 legislative chambers. (Why 99 chambers and not 100? Nebraska is unicameral.) In total, 6,066 legislative seats are up for general election in 2018 plus a handful of special elections to fill vacancies. That’s 82% of the nation’s 7,383 state legislative seats.

Legislatures not holding regular elections this year are the lower and upper chambers in Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia, where all legislative and gubernatorial elections are held in odd-numbered years, and the senates in Kansas, Minnesota, New Mexico and South Carolina, where all senators are elected at the same time, with their four-year terms falling this time with the presidential election.

The legislative landscape

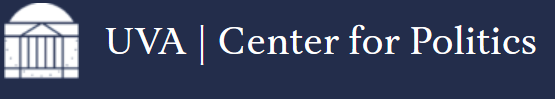

Republicans are at historically high levels of dominance in the states: 4,107 (56%) legislators are Republicans and 3,128 (44%) are Democrats, with 143 seats either vacant or held by independents or members of minor parties.

The GOP controls 65 of the 98 partisan chambers, Democrats hold 31, and two are tied—the Minnesota and Connecticut Senates. Nebraska is the outlier: Its “nonpartisan” 49 senators are elected without a “D” or an “R” listed on the ballot. Even though a majority of Cornhusker senators are registered Republicans, NCSL has historically honored Nebraska’s nonpartisan tradition and excluded the state from partisan tallies.

Chamber control is one measure; overall legislative control — when both chambers are held by the same party — is important too. Republicans currently hold both chambers in 31 states, Democrats have both in 14 states, and four states split (Nebraska is nonpartisan).

Those numbers don’t tell the full story, though. In Alaska, more Republicans were elected to the House than Democrats, but three of them (along with two independents) caucus with the Democrats, giving the Ds effective control and pushing Alaska into the split category. In New York’s Senate, it’s the reverse. Ds have the numerical advantage, but one of them caucuses with Republicans, moving it into the split category, too. If you count Nebraska as Republican and factor in both coalitions, the “real” legislative control numbers are 31 Rs, 13 Ds, and six split.

That’s a nationwide flip from just 10 years ago. After the 2008 election, Democrats controlled 27 legislatures, Republicans controlled 15 (including Nebraska), and eight were divided.

How high can a single party go? In the post-Watergate election of 1974, Democrats surged to control of 37 state legislatures, while Republicans ran the show in only four states: Idaho, Kansas, North Dakota, and Vermont (go figure).

Map 1: Current party control of state legislatures

Governors and state control

Republicans also hold a sizable majority of the governor’s mansions: 33 of the 50 governors are from the GOP, 16 are Democrats, and Alaska Gov. Bill Walker is an independent. Nearly a third of this year’s 36 governors’ races are considered toss-ups, with volatility in the polling for most of those races.

Putting the governors and the legislatures together, Republicans control all the power levers in 26 states, and Democrats in just six. That leaves 18 states with divided government.

Outlook for 2018

Several factors point to a good year for Democrats in the states.

Midterm elections are almost never good for the party in the White House and can be downright awful. In only two of the past 29 midterm election cycles going all the way back to 1902, did the president’s party not lose seats. Those two were in 1934, when the country was in the depths of the Depression and Democrats campaigned on the New Deal, gaining over 1,100 seats; and in 2002, when Republicans netted 177 legislative seats in the aftermath of 9/11 as the nation prepared for war in Afghanistan and Iraq. On average, the party of the president drops 412 legislative seats in midterms.

Map 2: Midterm seat change in state legislatures, 1902-present

Another reason Democrats are optimistic about Nov. 6 is that the election is likely to be a referendum on President Donald Trump. “All politics is local” is no longer true — even state legislative races are becoming increasingly nationalized. Democrats believe that the president’s historically low approval ratings point to a big surge for them. Trump is the only president never to have over a 50% approval rating going all the way back to President Truman, according to historic data provided by FiveThirtyEight.com. Trump’s approval rating on FiveThirtyEight’s average has stayed under 43% since mid-March 2017.

Trump’s lagging popularity probably helped Democrats pile up special election wins over the past 23 months.

In the 193 “specials” for legislative seats since 2016, Democrats have flipped 24 Republican seats, whereas Republicans have picked up just four seats formerly held by Democrats. Many of those Democratic wins were in districts where the president won by close to double digits. Special elections have typically been a harbinger of success in the general elections.

Plus, Democrats achieved stunning gains in the 2017 Virginia House of Delegates’ general election in 2017, picking up 15 seats in the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere and falling just one vote short of a tie.

GOP legislative candidates have worked hard to campaign on the surging economy touting the nation’s strong GDP numbers and very low unemployment rates. Republicans also know that they have a bulwark to protect them from a Democratic year — large legislative majorities in many chambers. In fact, in 16 Republican-held states, their majority is high enough to override a veto without assistance from the minority party. The same is true in just four Democratic-held states. One possible outcome in November is that Democrats pick up hundreds of seats but manage to wrest control in just a few legislative chambers. That would be something of a victory for the GOP.

Battleground chambers

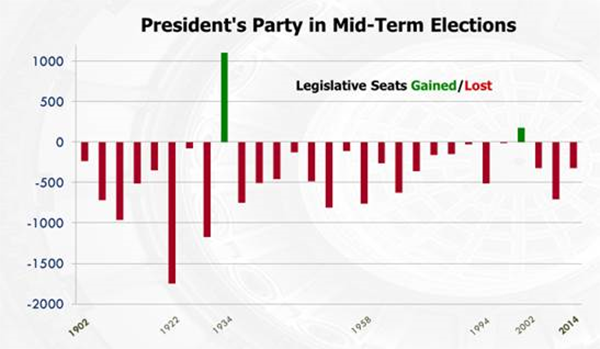

How many chambers are in play? On average, 12 legislative chambers flip control every two years. Democrats will almost certainly gain chambers in 2018 but may fall short of that average and are likely to gain far below the 22 chambers that Republicans took in the first midterm of Barack Obama’s presidency.

In six chambers Democrats could gain control by netting just two or fewer seats: the tied Connecticut and Minnesota senates, the Colorado and Maine senates, where Rs lead by one, and the Arizona Senate (now 17 R, 13 D) and the Wisconsin Senate (18 R, 15 D).

The chambers below are the ones to watch on election night for a possible party control shift:

Table 1: Battleground state legislative chambers, grouped by current party control

Notes: *The Minnesota Senate is tied 33-33. The outcome of a single special election will determine partisan control of the chamber. The New York Senate is nominally Democratic, but with one Democratic member caucusing with the Republicans, it is functionally under Republican control. The Alaska House is nominally Republican, but it is functionally under Democratic control because independent lawmakers and a Republican caucus with the Democrats.

P.S. Historic number of women candidates likely to lead to highest number of women legislators

More than 10,000 Americans are on the ballot this year to fill the 6,066 legislative seats on the ballot: 4,741 are Republicans, 5,349 are Democrats, and 719 are independents or from a minor party. Of the 10,000+ legislative candidates, 3,564 are women. That’s an increase of 28% over 2016. Women presently make up 25.4% of all state legislators nationwide, which is the most in U.S. history. That number is almost certainly going to go higher given the sharp increase in women seeking to join legislatures this year. Just over one-third of the women candidates are incumbents, with 2,265 of them running for open seats or as challengers to sitting legislators. Two-thirds of the women candidates are running as Democrats.

Another fun fact: 28% of this year’s legislative races are unopposed, much lower than in 2016, when 36% of seats went unopposed.

| Tim Storey is a division director at the National Conference of State Legislatures and its longtime elections analyst. Wendy Underhill is the director for elections and redistricting at NCSL. |