KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Our initial Electoral College ratings reflect a 2020 presidential election that starts as a Toss-up.

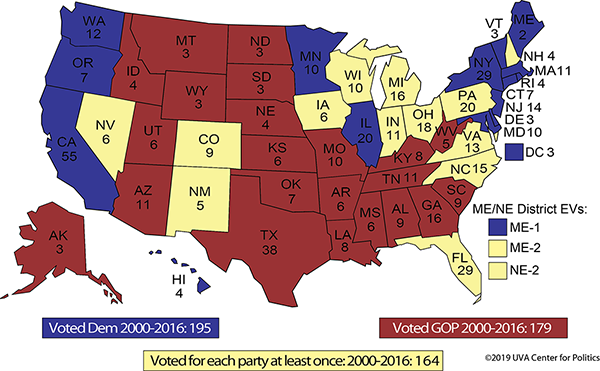

— We start with 248 electoral votes at least leaning Republican, 244 at least leaning Democratic, and 46 votes in the Toss-up category.

— The omissions from the initial Toss-up category that readers may find most surprising are Florida and Michigan.

— Much of the electoral map is easy to allocate far in advance: About 70% of the total electoral votes come from states and districts that have voted for the same party in at least the last five presidential elections.

The 2020 battlefield

With an approval rating in the low-to-mid 40s — and, perhaps more importantly, a disapproval rating consistently over 50% — it would be easy to say that President Trump is an underdog for reelection. The president won only narrowly in 2016 and did so while losing the national popular vote, making his national coalition precarious. He has done little to appeal to people who did not vote for him, and a Democrat who can consolidate the votes of Trump disapprovers should be able to oust him unless the president can improve his approval numbers in a way he has demonstrably failed to do in the first half of his term.

At the same time, the president’s base-first strategy could again deliver him the White House, thanks in large part to his strength in the nation’s one remaining true swing region, the Midwest. He’s an incumbent, and incumbents are historically harder to defeat (although it may be that incumbency means less up and down the ticket in an era defined by party polarization). Still, Crystal Ball Senior Columnist Alan Abramowitz’s well-regarded presidential “Time for Change” model, which projects the two-party presidential vote, currently projects Trump with 51.4% of the vote based on the most recent measures of presidential approval and quarterly GDP growth (the model’s official projection is based off those figures in the summer of 2020). Arguably, the state of the economy is the most important factor: If perceptions of its strength remain decent, the president could win another term. If there is a recession, his odds likely drop precipitously. Meanwhile, it’s not a given that the Democratic nominee can consolidate the votes of Trump disapprovers, particularly if a third party candidate (Howard Schultz?) eats into the anti-Trump vote.

As it stands, the state of the economy next year remains unknowable, as does the identity of Trump’s challenger (Trump himself remains very likely to be the GOP nominee, although there’s always the possibility that someone else may ultimately be the candidate). So what’s there to say about the Electoral College right now?

A lot, actually.

Take a look at Map 1. Over the past five presidential elections, states and districts containing 374 of the nation’s 538 electoral votes (70%) have voted the same way in each election. Map 1 shows the recent history of Electoral College voting, with places containing 195 electoral votes consistently voting Democratic this century and those containing 179 electoral votes consistently voting Republican. That may even understate the inelasticity of the current Electoral College alignment: For instance, it seems clear that Indiana’s 2008 vote for Barack Obama was something of a fluke, powered by Obama’s massive resource advantage there, John McCain’s neglect of the state, and a very favorable Democratic national environment. No one is listing the Hoosier State, which otherwise has voted Republican by double digits in the century’s four other presidential races, as competitive in a close national election. So if one adds Indiana to the GOP total, one can reasonably point to an electoral vote floor of 195 for the Democrats and 190 for the Republicans. At this early juncture, it would be surprising if either party fell below those tallies in November 2020, although some of the states shaded blue or red in Map 1 (like Arizona, Georgia, Maine, and Minnesota) could flip in 2020.

Map 1: Partisan consistency in the Electoral College, 2000-2016

This is a map that is reflective of where we think the race for the White House begins: as a Toss-up.

Map 2: 2020 Crystal Ball Electoral College ratings

The Safe Republican electoral votes (125)

We can divide these 20 small or medium-sized states into two categories: Interior West and Greater South. Or, we can also divide those same states in a different way: the old GOP bedrock, and the new.

Half of the states are those located west of Missouri and north of Texas in what one could broadly call part of the Interior West. These are states that have voted almost uniformly for the Republicans since Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 Democratic landslide. Starting in 1968, every one of these states has voted Republican for president in every election, with the exception of Montana, which narrowly voted for Bill Clinton in 1992. Montana is an outlier in another sense: It is the only one of these 10 states that currently has a Democratic senator. Any GOP nominee with a pulse — or probably even one without one — will carry all of these states.

The same is likely true of the other 10 Safe Republican states that one can broadly categorize as being part of the Greater South — with the exception of Indiana, which along with Missouri is the most culturally southern of the Midwestern states. This group contains many states of the old Confederacy that were once reliably Democratic and now are reliably Republican, along with Border States like Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia, all places where one-time Democratic strength has lapsed. Even long term, none of these states seem like particularly ripe picking for Democrats, although political trends are not always permanent.

The Safe Democratic electoral votes (183)

This category is swelled by mega-states California, Illinois, and New York, one-time swing states where the Democratic Party has a hammerlock thanks to massive Democratic margins in giant metro areas like Chicago, New York City, Los Angeles, and the Bay Area. These three states alone hold nearly 20% of all the electoral votes. The rest of the Safe Democratic states border the Pacific Ocean or are in the Mid-Atlantic or Northeast. Some of these states have featured close presidential results in recent history — for instance, George W. Bush only lost Oregon by less than half a percentage point in 2000 — but the last time any of them voted Republican for president was 1988.

Outside of a total Republican blowout victory, the likes of which do not seem possible in this particular era, all of these states will vote Democratic in 2020. One state to watch in the long term, though, may be Rhode Island. The Ocean State has been much more Democratic compared to the nation in the lion’s share of elections since the New Deal political realignment, which in Rhode Island really started with the 1928 Democratic nomination of Al Smith. But Hillary Clinton’s showing in Rhode Island was one of the weaker ones for a Democrat there in recent history. The Democratic presidential margin there fell from 27.5 points in 2012 to 15.5 in 2016. That doesn’t mean much, if anything, in the short term, although if Rhode Island ever becomes more of a swing state, we may look back at 2016 as a very early sign.

The Leans Republican electoral votes (123)

These states will help determine whether the election gets away from Trump or not; put another way, if a Democrat wins any of them, the election is likely over.

This category includes five of the nine most populous states: Texas, Florida, Ohio, Georgia, and North Carolina. Of these states, the Sunshine State is the one that is most arguably a Toss-up. After all, Trump only won the state by about a point in 2016, and Barack Obama carried it twice, including by about a point in 2012. And yet, we’ve seen Republicans, again and again, eke out very close victories in the state, including for Senate and governor in 2018. While we don’t want to put much weight on the midterm results — they just aren’t historically all that predictive of what’s to come in the presidential — we have to say that the fact that the Republicans won both statewide elections, including defeating incumbent Sen. Bill Nelson (D), was eye-opening to us. It’s easy to explain away the other Democratic Senate losses in 2018, which came in the heavily Republican states of Indiana, Missouri, and North Dakota: Democrats probably didn’t have much business holding those seats anyway, and the luck those Democratic incumbents enjoyed in 2012 ran out in 2018. But Florida, a bona fide swing state, voting Republican for Senate, too? We know that Nelson was a weak incumbent whose age was showing, and that now-Sen. Rick Scott (R) was an unusually strong and well-funded challenger in a year like 2018. Still, Scott winning was, it has to be said, one of the great electoral oddities in midterm Senate election history. As Alan Abramowitz pointed out after the election, Scott’s performance in Florida stood out: It was the only state where his basic model predicting 2018 Senate results based on a state’s partisan lean and incumbency showed that the GOP clearly should have lost, but didn’t.

This decade, Florida has featured two presidential contests, three gubernatorial races, and one Senate race each decided by a margin of 1.2 points or less. The Republicans won all but one of those races. Are the Democrats just unlucky, or does the GOP have a very small but steady edge in Florida?

To start this cycle, we’re going to assume the latter in our ratings.

The other electoral votes in this category can be divided into two groups: growing Sun Belt states that typically are more Republican than the national average that may be becoming less reliably Republican (Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas) and Northern locales that may be getting more Republican, thanks in part to Trump’s appeal among white voters who do not have a four-year college degree (Iowa, Ohio, and Maine’s Second Congressional District, which covers much of the state’s land area). Again, we suspect that a Democratic win in any of these places would be part of a Democratic national victory. The question then becomes how the Democratic nominee opts to use his or her resources: In a state like Iowa or Ohio, which has more recent history voting Democratic but may be trending the other way, or in states like Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas, which may eventually be part of the Democratic coalition but may be difficult for the Democrats to pry away from Trump in the short term. Different Democratic nominees will have different opinions about these strategic questions.

There are no electoral votes that start in the Likely Republican category.

The Leans and Likely Democratic states (61)

All of these states but one — Michigan — voted for Clinton in 2016, and the Wolverine State featured her closest loss, .22 points in a state we think her campaign indefensibly neglected. Our sense in 2016, and now in the wake of 2018, was that Michigan was Clinton’s flukiest loss and that the Democratic nominee should start as a marginal favorite to recapture it. Electoral watchers who want to focus on some key counties this cycle should look at Kent County, Michigan, home of Grand Rapids. The traditionally Republican county is the state’s fourth-largest source of votes, and it was one of only a few counties in Michigan where Trump’s margin was weaker than Mitt Romney’s in 2012 (and, remember, Trump ran nearly 10 points ahead of Romney’s Michigan margin overall). Trump carried Kent County by about three points, or about 9,500 votes, in 2016. While one can slice the electorate any which way to make an argument, that Kent County margin almost accounted for Trump’s roughly 10,700-vote statewide victory. Democratic Senate and gubernatorial candidates won the county in 2018, a historical rarity in Michigan. A possible Democratic trend there, and in some parts of greater Detroit, very well could be enough to flip the state back blue even as Democratic performance continues to wither in other, more rural parts of the state.

Those who think we are being unfair to Trump by making Michigan Leans Democratic should consider whether we are perhaps being unfair to the Democratic nominee by making Florida Leans Republican. Ultimately, we’re just trying to reduce the number of Toss-ups where we feel that’s warranted. Just as we think Florida going blue would probably mean a Democratic presidential victory, so too do we believe that a Republican win in Michigan probably would mean that the GOP is retaining control of the White House. So if we move either to Toss-up, it may mean that a favorite is emerging in the presidential race overall.

Colorado and Virginia, to us, are trending Democratic although they are still competitive. Trump winning either would be suggestive of his winning a much clearer victory than in 2016. Maine’s two statewide electoral votes and Minnesota as a whole may be getting more competitive over time, but Trump’s narrow statewide losses in 2016 may have been partly a function of relatively high third-party voting in each state. Trump finished slightly under 45% in each state and Democrats did well in both last November, two other factors that prompt us to start the Democrats as favorites in both. Nevada may be the Democrats’ version of Florida: Extremely competitive but ultimately harder for the other side to win.

New Mexico, alone among the states mentioned here, starts as Likely Democratic; while George W. Bush narrowly won it in 2004, the nation’s most Hispanic state has voted Democratic by eight to 15 points in the last three presidential elections. We think the Democrats should be OK there no matter how many rallies Trump holds in nearby El Paso.

The Toss-ups (46)

We close with the final 46 electoral votes, the Toss-ups. They come from four states — Arizona, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — as well as one congressional district, Nebraska’s Second, which is based in Omaha. Clinton carried New Hampshire by less than half a point in 2016; Trump won the rest, by less than a point in the case of Pennsylvania and Wisconsin and by 3.5 points in Arizona. If it seems like we’re splitting hairs by rating Michigan as Leans Democratic and Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as Toss-ups, we have to admit that we are. But Trump’s margin in the latter two were a tiny bit bigger than his margin in Michigan, and we think the Democrats’ path to victory in Michigan is more solvable based just on slightly better turnout, whereas the Democrats may have a little more persuasion work to do in the other two former “Blue Wall” states. Also, Democrats have generally done a little bit better in Michigan than in the other two over the past couple of decades.

Arizona, to us, is the best target for Democrats among the usually Republican Sun Belt states that have been becoming more competitive (a group that also includes Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas). Arizona’s voting is dominated by Phoenix’s Maricopa County, one of the nation’s only very populous counties that is gettable for a Republican presidential candidate. But the trendlines for Republicans in such counties are generally poor, a factor that can’t be discounted in a country where local political eccentricities are increasingly being overtaken by one-size-fits-all trends.

Indeed, these national patterns, and how they manifest themselves at the local level, will help determine this election. Larger anti-Trump trends in the big cities and suburbs could be canceled out by even bigger Trump landslides in the vast rural and small-city swathes that cover much of the most competitive states. Voting within these states is becoming more polarized on urban vs. rural grounds, but the sum total of those changes add up to an Electoral College battleground that can tilt either way.

Readers who want to game out the Electoral College can use the great interactive tools at 270ToWin.com or Taegan Goddard’s Electoral Vote Map.